News of the Day

Special Collections digitizes entire run of the Maine Campus newspaper

By Pauline Bickford-Duane and Brad Beauregard

In Massachusetts, a researcher at MIT hopes to verify that a well-known artist visited the University of Maine early in her career. In the Midwest, a UMaine alumnus searches for old photographs of his family members. Here in Maine, several former classmates reminisce on their early writing careers with photos shared across Facebook profiles.

All of these stories have varied origins, but one thread ties these pursuits together: a newspaper. Each of these efforts led to the Maine Campus archives held by Fogler Library.

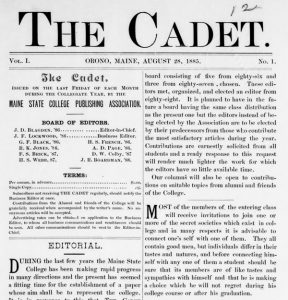

The Maine Campus, the University of Maine’s official campus newspaper, has been in operation since the 1800s. Issues dating to the earliest days of the newspaper are preserved by the Special Collections Department at Fogler Library. But until recently, the issues were only available on microfilm, making access cumbersome and often impractical for people around the country.

Soon, with the completion of a digitization project that’s been in progress for more than a year, the entire run of the Maine Campus will be available online.

The Maine Campus is a well-known title to the University of Maine community. The student-run newspaper was founded in the late 1800s as the College Reporter. The newspaper went through several name changes before settling on the Maine Campus in 1904. Throughout its history, the Maine Campus has experimented with different publication schedules. Originally published monthly, the paper increased in frequency periodically until the 1980s when it became a daily newspaper for a short time. For most of its history, the Maine Campus has been a weekly publication.

Despite its changes in name and format, one aspect has remained constant in the 140-year history of the Maine Campus: the newspaper is entirely student-run. Students write articles and conduct interviews. Students make editorial decisions. Students decide when and how often to publish.

Thanks to its student leadership, the Maine Campus has been able to provide an immediate window into the stories, concerns and interests of the University of Maine for nearly a century and a half. Taken as a whole, the publication offers a unique perspective for researchers and alumni across the country.

For years, Richard Hollinger, head of Special Collections, saw the Maine Campus archive as an opportunity to take a large, useful collection and expand its audience.

“I’ve wanted to pursue the [Maine Campus] project for about 15 years,” says Hollinger. “Other large universities have digitized their campus newspapers, and I knew the archives would be widely used both by researchers and campus administrators.”

As Hollinger explains, the archives hold value for anyone doing research related to the campus or the greater region. Newspapers, in particular, offer a useful set of records.

“A newspaper is information-dense,” says Hollinger. “There’s often more granularity than novels or books. Articles contain a lot of information in a small space. It’s not a coincidence that newspapers get a lot of attention from archival institutions.”

The Maine Campus archives have always had potential value to researchers, but access was limited. In the past, researchers would need to visit Fogler’s microfilm room or contact Special Collections directly to look into anything from the archive. If researchers knew the date of a specific event, they may have been able to locate those issues in the Maine Campus microfilm. Even then, this would require a line-by-line reading of the articles to search for any mention of the subject, if it existed at all.

Bringing the Maine Campus archive online would allow researchers to view the materials from anywhere in the world. But, digitizing 5,000 issues of a newspaper that dates back to the 1800s is a complicated, time-intensive and expensive undertaking. When a donor made a gift to Fogler Library, Hollinger and his staff could finally pursue the project.

At his desk in Special Collections, Library Specialist Paul Smitherman navigates between a pair of computer monitors as he uploads issues of the Maine Campus to the Digital Commons, an online repository for UMaine creative, scholarly and historical materials. For the past several months, the Maine Campus archives have been one of Smitherman’s daily priorities.

“We can upload about 100-150 issues at a time,” says Smitherman. “I’m working on the 1980s now. The goal is to finish them by the end of the year.”

Digitization — the process of making a physical item available electronically — can take many forms, ranging from scanning a book or a photograph to creating an interactive 3D model of a building. Digitizing a large collection like the Maine Campus, however, wasn’t as simple as scanning and uploading an image, especially when considering the dates of the issues and the different mediums they were recorded in.

Every page of every issue needed to be scanned. The Maine Campus archive contains over 5,000 issues, many of which were stored on microfilm. Scanning and cataloging decades of microfilm is a complicated process on its own, but without an additional step, those scans would just be photos. For someone to find anything in the archive, they would still need to read individual issues page by page.

Every page of every issue needed to be scanned. The Maine Campus archive contains over 5,000 issues, many of which were stored on microfilm. Scanning and cataloging decades of microfilm is a complicated process on its own, but without an additional step, those scans would just be photos. For someone to find anything in the archive, they would still need to read individual issues page by page.

To make the issues searchable, Optical Character Recognition software “reads” the document and creates a text-only version of it, pulling the words from the image. OCR technology has a myriad of benefits, not least greater accessibility. For example, patrons with impaired vision can download a text-only file in order to enlarge the text or use external programs that will read the text aloud.

OCR also makes the text searchable, meaning search results will pick up individual words found in the text. OCR enables users to find what they need in seconds without having to manually skim the pages.

Because of the size of the archive, Fogler Library outsourced the scanning work to a company that specializes in digitizing newspapers. Once the digital files were ready, Smitherman and others uploaded the archives and wrote the metadata for individual issues. Metadata, or, put simply, “data about data,” can include fields like a title, date, author and institution. This information makes it easier for users to find specific topics or subjects within the archive once it’s online.

The end result is a complete archive of the Maine Campus newspaper that’s fully available online.

At first impression, a campus newspaper can seem narrow in scope. Taken in isolation, any individual issue might cover relatively mundane topics: the score of a basketball game, the weekly events on campus, or coverage of a visiting artist’s gallery.

Even though the Maine Campus’ coverage focuses on UMaine and the Orono region, the newspaper has never operated inside a bubble. Desiree Butterfield-Nagy, an archivist in Special Collections at Fogler Library, explains that campus newspapers often reflect not only local issues but the broader social and cultural issues that echo across the region.

“The Maine Campus is more than a campus newsletter,” says Butterfield-Nagy. “It has investigative reporting. It reflects political issues, budgeting directions [and] the allocation of state funds and resources.”

Taylor Abbott, current Editor-in-Chief of the Maine Campus, says the newspaper’s dedication to research and quality journalism is part of its culture, and she believes the archives can help reflect that.

“Many do not know how resourceful the Maine Campus is,” says Abbott. “I hope that as more people discover the archives, the more they know that they can count on us. The entire staff at the Maine Campus takes a lot of pride in the researching and writing that we do.”

As a whole, the archive provides a window both to what happened and how people at the time felt about the world around them.

“Newspapers cover a broad spectrum of subjects and readers and writers,” says Hollinger. “They provide chronology. Almost any major initiative or event will be documented in a newspaper.”

This broad-spectrum is evident across individual issues and whole decades of the Maine Campus. In an issue from October 1957, you can read about Halloween pranks or the outbreak of the flu across campus. On a broader scale, you can read the papers through the 60s and 70s and trace the line of anti-war demonstrations and civil rights protests that occurred on college campuses across the United States.

Beyond its significance as a cultural lens, the newspaper also provides a potential data point for researchers. For example, researchers have used articles to identify some of the state’s earliest radio broadcasts and place them in the context of the broader movement toward the creation of National Public Radio, and students have analyzed strategies and remarks of political figures who include campus as a stop on the campaign trail.

While its value to historical research is clear, the Maine Campus is, at its core, a catalog of people at a particular place during a particular time. For that reason, the paper holds value for anyone who has been part of the University of Maine community as a student, a professor, a staff member or a visitor.

With some collections, the impact is more clearly visible from the beginning. The Maine Campus, however, walks a line between what we know is of historic value and the items of value that we haven’t yet discovered. Until the research is finished, until the questions are asked, we cannot know what someone might be able to trace back to an article in a small newspaper in Maine that was published years, decades or a century before.

This story was originally featured in the 2018 Raymond H. Fogler Library Magazine.